Some Eerie Reading

“Bank failures are caused by depositors who don’t deposit enough money to cover losses due to mismanagement” – Dan Quayle (Maybe he was misquoted...?)

Before we begin this week’s post I wanted to remind you that I’m open for your questions about bank safety, the security of your deposits, and so forth. We’ll touch on these topics below but know you can always ask questions.

Beyond that, I have to say it was eerie to read about another hasty merger over the weekend to keep a bank from failing. This time it was Swiss regulators arranging a marriage of the failed investment bank, Credit Suisse (CS), to UBS, the largest of that country’s banking institutions.

Back in September ’08 it was weekend news that BofA was buying Merrill Lynch, the world’s largest retail brokerage at the time amid nasty and worsening market and economic conditions. Both Merrill and CS failures resulted from years of bad risk management but, in the case of CS, also the bad luck of showing the last of a lengthy string of big losses while investors are in the mood to punish.

It’s natural for news like this and of recent bank failures to seem like the opening act of another Global Financial Crisis. There’s lots of uncertainty, investors are skittish, and the trust we give to these institutions can seem misplaced. But is this another 2008? While predicting something like that is far beyond my ability (or anyone’s, quite frankly), this latest news is different and it’s too simplistic to lump the failure of CS in with the seizure of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and what may be the final throes of First Republic Bank.

Here are some points on this from my research partners at Bespoke Investment Group (italicized below) that I’m cobbling together. Unitalicized notes are from me.

A good and simple explanation…

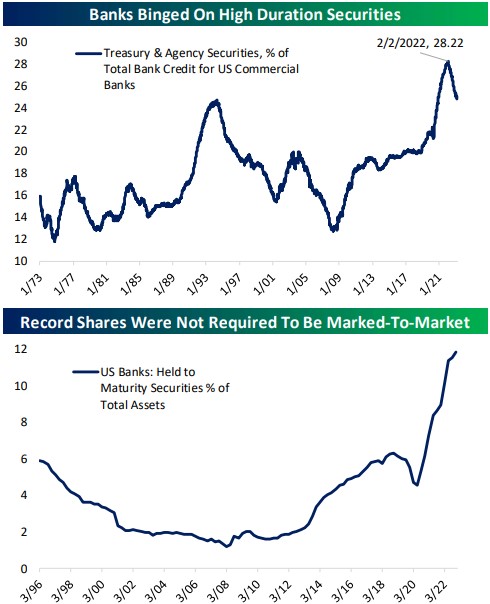

During the pandemic, enormous fiscal transfers and Federal Reserve QE of government bonds meant an enormous buildup of deposits in the banking system. Those deposits were created by either issuance of government bonds or by purchases of those bonds, financed by bank reserves which match with deposits. Banks faced with those massive inflows of deposits generally bought government bonds. Unable to invest in riskier securities or grow loans rapidly thanks to macroprudential regulation (ironically, largely a regulatory response to banks being too risky leading up to the Global Financial Crisis), banks were forced to buy low credit-risk government bonds.

While those bonds don’t have a credit risk, they do have duration risk. As long as banks aren’t forced to sell them thanks to ample deposits, they do not have to recognize a mark-to-market loss on those holdings (the “held to maturity securities” reference in the chart below). But for banks that are under deposit pressure, things can get out of hand quickly. Concentrated crypto deposits (like at Silvergate or Synchrony) or exposure to specific demographics (like at Silicon Valley Bank or to a lesser extent First Republic) that fled quickly led to stress and ultimately a need to wipe out equity, though for now the total losses remain unclear.

(An interesting side note to this whole thing is how focusing on liquidity, whether for your household or the bank you might manage, is foundational to your financial success; mess with it at your peril.)

On to CS – much less a function of the charts above and more from bad timing and fed-up investors…

…In the press conference on Sunday discussing the shotgun ‘merger’ between Credit Suisse and UBS, regulators and officials of the banks cited the turmoil in the US banking sector as the reason for Credit Suisse’s demise. There’s always a need for a scapegoat, but to blame regional US banks for Credit Suisse’s downfall is a stretch. For now, let’s put aside the fact that just last week Credit Suisse announced an $8 billion loss in its delayed annual report. The bank noted that “the group’s internal control over financial reporting was not effective,” and its auditor PriceWaterhouse Coopers gave the bank an ‘adverse opinion’ with respect to the accuracy of its financial statements. Well before the SVB failure, Credit Suisse was already a dirty shirt.

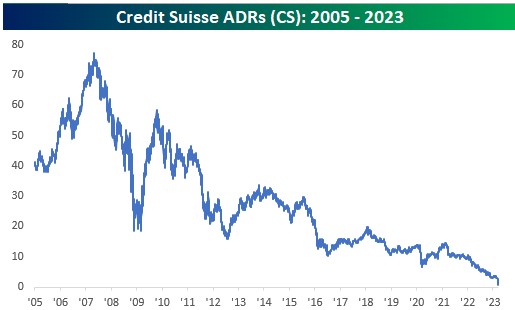

Just look at the stock price. From its peak of over $77 per ADR in 2007, Credit Suisse (CS) has been in a long downtrend. After bottoming at just under $19 in early 209, the share price quickly tripled over the last six to seven months, but the bounce was short-lived. By 2012, the share price was back below its Financial Crisis lows and in the ensuing years, any rally attempt quickly ended with a lower high followed by a lower low. The collapse of SVB and stresses on other US banks may very well have been the straw that broke Credit Suisse’s back, but if the bank had proper internal controls in the first place maybe it would have noticed the pile of hay on its back in the first place.

So, the problems of CS seem only loosely connected to the regional bank news we’ve been seeing here at home. But news of bank failures comes on the back of inflation and rising interest rates, volatile markets, and an economy that one day seems strong only to show weakness another.

Crises never play out the same way twice, of course. There are more banks flush with deposits and sitting on bond market losses they’d rather not be forced to realize. As I write, First Republic Bank’s stock price is down to about $12 after trading at nearly $150 a month ago and the bank is in emergency talks with JPMorgan and others. Maybe First Republic gets through this, but the damage is done.

The Fed has come to the rescue and big banks are getting bigger. A narrative of the system protecting itself (or eating its young) seems to mollify investors. Broad market indexes were higher yesterday amid all this news and, at least as of this writing pre-market Tuesday, prices are set to rise again. That’s good to see in the short-term but risks remain. We’re still likely heading into a recession of uncertain severity that, in a sense, seems like a natural result of the wild swings our economy has been through in recent years. But I’m going to cross my fingers and knock on wood while walking out on the limb to say that the wheels aren’t coming off of the global financial system anytime soon.

Have questions? Ask us. We can help.

- Created on .