Rewriting the Rules

Rules of thumb are helpful at distilling complex information into understandable tidbits of advice. They’re not intended to be an accurate application of all relevant information, just general guidance. The problem is that if left unchallenged long enough, rules of thumb can begin to seem like infallible truths. Helpful and important details can get glossed over or left out entirely. This happens a lot in the complex world of financial planning and investing.

Case in point is the rule of thumb that retirement savers should put as much as possible into tax-deferred accounts, like 401(k) plans and IRAs. These “traditional” accounts help folks save for retirement with the bonus of tax deductions along the way. Everybody likes a tax deduction, right? Then the account isn’t taxed until later and your savings can compound over time to create a sizeable nest egg if you play your cards right.

That’s the good part. The bad part, and what the rule of thumb glosses over, is how every dollar you withdraw in the future gets taxed as ordinary income. It glosses over mandatory distributions beginning at age 72. And it glosses over the taxes that your beneficiaries will have to pay when they ultimately withdraw. All of this is traded for the powerful incentive of a tax deduction on contributions. It works well, don’t get me wrong. But it’s imperfect.

The alternative is investing in a Roth IRA. I’m sure you’ve heard of these. They function like traditional accounts with the difference being when you pay taxes. With a Roth you don’t take a tax deduction as you save so you don’t need to pay taxes on the money in the future, maybe ever. Roth accounts were created in the late-90’s and took a while to get traction, so retirement savers haven’t had as much time to accumulate money in these accounts. This is probably a big part of why the old rule of thumb didn’t include them.

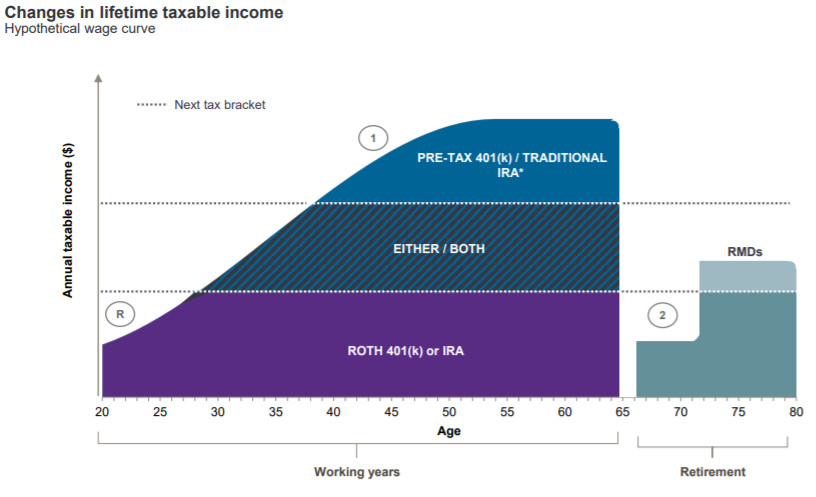

But this is changing as retirement researchers (and your humble financial planner) question some of the industry’s core assumptions. For example, researchers at JPMorgan demonstrate how the younger someone is and the lower their tax bracket, the more value they get from Roth accounts. Savers should only think about contributing to a traditional account as they age and make more money (and pay more taxes). The following chart illustrates this.

Continue reading...

The reason has to do with what happens down the road during retirement. Since every dollar withdrawn from traditional accounts is taxed as ordinary income, it stacks on top of Social Security, pensions, part-time work, etc. This leads to what’s referred to as “bracket creep” and causes higher tax bills. Paying higher taxes makes retirement more expensive. If not controlled, bracket creep can limit tax deductions and, at higher income levels, cause you to pay more for Medicare. All of this drains your savings faster and makes your retirement less secure.

Again, younger savers can avoid this problem by only funding Roth accounts. This is likely an option within their plan at work. If not, the plan needs an update and they should ask their HR department about it.

It gets more complicated for older savers, however. As folks look at starting Social Security and taking retirement account distributions, they should test for bracket creep by running tax projections. This is baked into many financial planning software packages and is relatively easy to do.

It’s not uncommon to see a married couple in the 24% or 32% federal bracket while working drop all the way down to 10% in the first year or so of retirement. Taxable income falls when the paychecks stop and living off cash at the bank generates an extremely small amount of taxes. But then after a while income starts to climb. One spouse starts drawing Social Security and then the other starts sometime later. Then one begins taking Required Minimum Distributions (RMD) from their retirement accounts and a couple years later the other spouse follows suit. Before they know it, they’ve creeped up from 10%, to 12%, to 22%, or higher brackets.

There’s a way around this, however. If you missed the boat (as many have) on making contributions to Roth accounts, you can still do Roth conversions. The idea here is a counterintuitive one. You’ll withdraw money that’s already in your traditional retirement account, pay taxes on it now, and then put the money into a Roth so that you don’t need to pay taxes later. If done right, this reduces your total taxable income in future years by keeping you in a lower tax bracket. Essentially, you’re restructuring future retirement income by prepaying taxes.

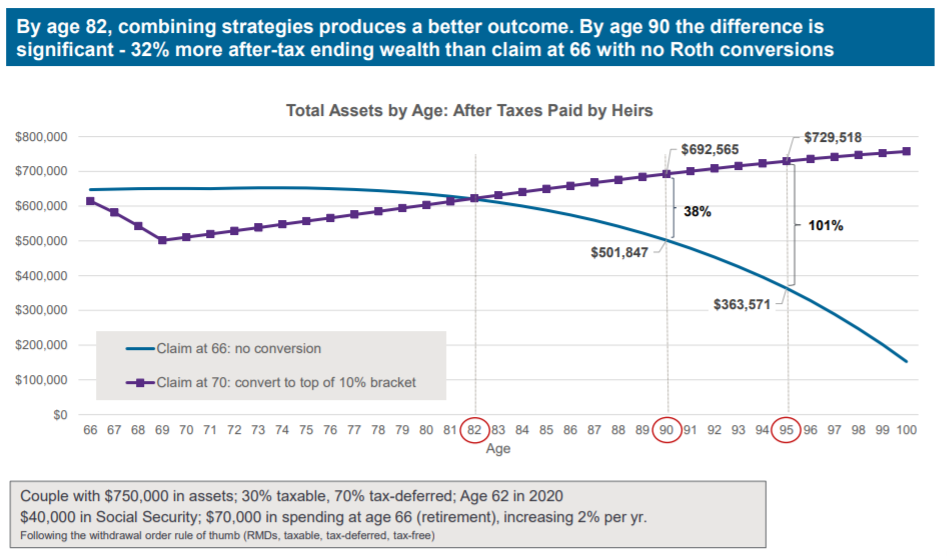

The rub here is that bracket creep is always possible, so you’ll want to look at conversions when you’re having a low-income year. The idea is to do conversions incrementally while staying in your typical tax bracket. Maybe it’s now due to the coronavirus. Or maybe it’s done as part of a more creative plan to retire earlier, live off other savings, delay Social Security until age 70, and do Roth conversions aggressively during the years between. This kind of thing can make a serious dent in future taxable income, reduce total taxes paid, and leave money in your retirement accounts longer. The chart below from JPMorgan illustrates how a retiree’s balance could behave while following this approach.

So, the rule of thumb about cramming your savings into traditional retirement accounts is certainly helpful but potentially sets you up for higher taxes later. If you’re younger, look instead to Roth accounts as your primary savings vehicle. If you’re nearing or in retirement, look closely at the counterintuitive process of Roth conversions. It will likely save you money in the future.

Have questions? Ask me. I can help.

- Created on .