Thinking About Yield

Some years ago I did a short series of posts defining some key finance and investing terms. Looking back I don’t see that we discussed a critical concept, especially these days with rising interest rates: yield.

Yield is one of the words in the English language that has multiple meanings depending on the context. We yield to oncoming traffic when driving our car or, if we’re a farmer, our lands yield crops. While the fundamental meanings of yield probably seem obvious, the term can get muddy pretty quick in my realm. Let’s get into the details of how we think about yield in an investment context.

The yield of a stock investment is pretty straightforward. Say XYZ Corp offers a dividend to shareholders each calendar quarter of $1 per share and you paid $100 to buy one share. After receiving your first dividend you could say that your yield is 1% but hold the share for a year (four quarters) and your yield is now 4% and should be expected to remain so until XYZ Corp changes its dividend policy, or you sell your share.

That math is pretty simple. Where it starts getting interesting is when the value of XYZ Corp shares moves around with the markets and you keep buying. Maybe you bought more shares at $90. Your $1 dividend on the new purchase is now a 1.11% yield per quarter, or 4.44% per year. This gets blended with your original $100 purchase to equal 1.05% quarterly and 4.2% per year. Then this gets complicated further if you reinvest your dividend, perhaps buying fractions of a share at whatever the current price happens to be.

Fortunately we have software to keep track of all this stuff, but one takeaway should be that your yield is a function of the cash you’re receiving while holding shares and what you paid to buy the shares. It’s not your investment return when we talk about stocks because, at least in theory, the growth potential is limitless.

So that’s stocks, but let’s look at bonds because that’s where yield is most important. Rates have moved around a ton in the past year and the dynamics of yield in the bond market can be confusing. Let me explain.

In our example above XYZ Corp has announced a dividend that’s not reflective of the company’s share price, just what management is giving back to shareholders and there’s no legal requirement for them to do so.

But this is different with most bonds. Bonds, as you’re likely aware, are debt obligations that come with strict requirements to pay a set rate of interest for a set timeframe before paying off the debt at maturity.

Take Treasury bills, notes, or bonds (all hereafter referred to generally as “bonds”) as an example because it’s simplest.

The US Treasury borrows money by issuing bonds across a range of maturity periods. Let’s assume you bought 10yr bonds brand new on www.treasurydirect.gov that pay 3.5% interest each year until maturity. Assuming you spent the interest your yield would be the same as your interest rate, or 3.5%. This would also be your investment return each year you hold the bond. Pretty simple.

Just as with stocks, however, there is an active secondary market for many bonds, especially US Treasury securities. According to SIFMA, an industry organization, as of January the daily average trading volume for Treasuries was at least $615 billion. Among other things, this means you can see your bond’s value change in real time and can readily sell if needed.

Since we’re usually buying bonds in the secondary market understanding our yield becomes more important than the interest rate that bonds pay. The reason is that we’re almost never buying bonds at the original issued value of $1,000. Instead, we buy or sell at a premium or discount that’s constantly changing due to market conditions.

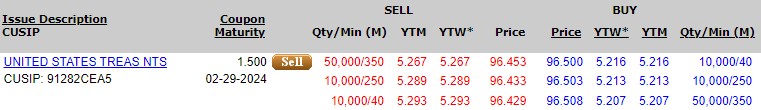

Here’s what this looks like in practice. This screenshot is from the system I use to find and buy individual bonds and looks at a Treasury Note maturing in about a year.

You’ll see that the interest rate is only 1.5% but the Yield to Maturity is about 5.2%. The higher yield, as mentioned above, is a function of the bond’s interest rate and the price you paid to buy it, in this case $965 instead of the original $1,000. While holding the bond you’d receive the 1.5% per year, paid every six months. But then at maturity you’d get $1,000, not the $965 you originally paid. That’s the discount coming back to you and is what bumps up your yield.

We’ve been discussing individual bonds so far and most of you own bond funds instead. Funds have lots of benefits over owning the individual bonds and are best thought of as everything we’ve already discussed but spread across hundreds or thousands of bonds in a portfolio. Instead of a defined maturity date, bond funds are perpetual and are often grouped together by different maturity periods (short-term, medium-term, and so forth) and issuer type (US Treasury, publicly traded corporations, etc).

I could go on, but I try to keep these posts on the shorter side. In any case, the main point is that, as investors, our yield is the cash flow we’re getting from our investments adjusted up or down based on what we paid to buy the investment and is a critical factor when thinking about bonds.

Have questions? Ask us. We can help.

- Created on .